Back in the days before COVID, I was looking for ideas to enhance my social justice curriculum in Grade 4. I was also curious to see how I might bring more of my own Ghanaian culture into the classroom, expanding the lens through which my students could see the world. When the opportunity arose to travel to Ghana as part of the Witness Tree Institute of Ghana (WTIG) program for educators, I was excited, applied, and was accepted – only to have the trip canceled when the world shut down in the pandemic.

By the time I reapplied for summer 2022, I was teaching Grade 5. Now as a Grade 5 Humanities teacher, I am teaching immigration and social justice. The program worked perfectly, and tapped into my own immigrant roots going back to Ghana and Nigeria.

Witness Tree Institute is “an immersive two-week professional development experience in Ghana for K-12 educators to deepen their knowledge of African culture and its impact on the world, and to explore their pedagogical competencies” (witnesstreeinstitute.org). It was created to engage educators in multidisciplinary learning experiences through travel, and through exploring Ghanaian culture and history. When many students think of “Africa,” they don’t recognize that it’s a continent, made up of many countries and cultures. They carry assumptions about “Africa” – that it’s all about safaris, or that it’s made up of poor people walking miles to get water. How might teachers bring a fuller sense of culture to their classrooms? How might that support deeper conversations about the cultures we encounter – including American culture – as each child learns to talk about where they are from, creating space for them to open up about what makes them special?

Over the course of 14 days, my fellow educators and I traveled across Ghana, learning songs of celebration and pride, dancing to traditional drumming and other instruments, exploring the science of plant medicine and cocoa production, and collaborating with Ghanaian educators. Among the life changing and unforgettable opportunities the trip provided, was our visits to the Cape Coast and Elmina Castles that imprisoned the enslaved. Those tours were very emotional. Fellow travelers were from all over the United States, Black and white educators. We had very rich discussions about our individual experiences as Americans and our sense of African history (or lack thereof).”

When we went to the Donkor Nsuo Slave River [one of the markets for gathering indigenes during the trans-Atlantic slave trade], we encountered a group of students from a Ghanaian private school who were also learning about the history. We all took our shoes off to walk down the river where they bathed the enslaved before putting them on ships. It was very spiritual to walk on the paths of my ancestors. It took me back – this feeling of connection with them. The experience affirmed a deep part of my own identity–as a teacher, coming back, knowing more of who I am, having been through this journey, has made me a better educator, a better person. It was life-changing and empowering.

Being there in that place was mind-opening in unexpected ways. Everyone looked like me! It was different, but welcoming. I felt like I belonged. Some of the white educators in our group noted that it was their first time experiencing being the only white person in a group, and it gave them a new appreciation for being the minority.

These experiences threw my understanding of what it means to belong into sharper relief. At Park, I teach a unit on “belonging–” What does it mean to belong? That’s one of our year-long essential questions. We talk about it through the books we read, and when we talk of immigration, we ask, ‘Do immigrants feel they belong?’ This new perspective made the experience of belonging feel sharper, more personal.

As part of the journey, I had the chance to learn first hand from natives about their culture and history through music, dance, art, and food, and was able to bring back to my students a much more dimensional appreciation of the lives they live to replace their preconceptions. I showed them the hotels we stayed in, the people who work there. There is a range of people, lifestyles, and economic status. Being able to come back and talk to them about that was validating.

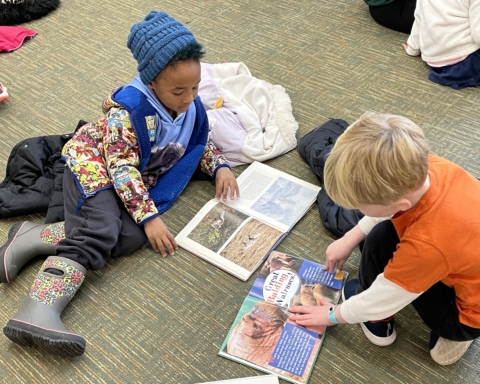

Each educator in our group planned curriculum ideas to bring back to their classroom. I focused on Adinkra symbols – popular Ghanaian symbols that represent concepts or aphorisms. I invited each of my students to choose a symbol and to write down what it represents. With the help of Elena Pereira in Park’s library, the students worked to cut out their symbols and affix them to fabric. The result: a mosaic of symbols, resembling a quilt, representing them as a community of people all coming together with their different representations and connections. Having learned the meaning of the symbols, I now recognize them when they crop up in art, media, movies, and more. For example, while watching the movie, “Black Panther,” I said “Hey! There’s the perseverance symbol!” (among other symbols and representations of African culture)

Another useful takeaway came from workshops on the meaning of African proverbs. This year, Grade 5 students would be reading Home of the Brave, about the Lost Boys of Sudan. It’s a book in four parts, and each part opens with a proverb. Grade 5 students are learning to interpret proverbs, so I started the year talking about proverbs early in September. We discussed what each proverb literally means, and then asked, “What lessons can you learn from it?” We worked to build interpretive understandings of each one. By the time students were reading Home of the Brave later in the fall, they were ready to work with each proverb and understand their relevance to the story.

WTIG gave me a community of fellow travelers – a cohort of colleagues from my trip with whom I’ve created this lifelong connection. We stay in touch, have a book club, celebrate birthdays, and share an invaluable and transformative experience. I love that I shared this with them.

Looking back, I know the experience definitely leaned into being a joyful learner. It strengthened my courage to teach things that are important to me that I think would be important to students, and that help them grow as responsible citizens.

~

Yet Ghana shows its might and power

Not in its color nor its flower

But in its wondrous breadth of soul

Its Joy of Life

Its selfless role

Of giving.

-W.E.B. DuBois

By Tasha Summers, Grade 5 Humanities Teacher and Advisor