Think back to your early days of elementary school – Do you remember learning to read? If you don’t, reading probably came easily to you. If you do, reading was probably more of a challenge. Research shows that about 80% of students learn to read with relative ease as long as they are provided with instruction that includes explicit and systematic phonics instruction. For the other 20% of students, specialized intervention as well as additional time and practice are necessary for skilled reading to develop.

The vast body of research collected from the past five decades from the fields of psychology, education, neuroscience, and linguistics, among others, known today as the Science of Reading, tells us that learning to read is a highly complex process. Although our brains are wired for speech, they are not wired to read. New neurological pathways need to be developed in the brain for skilled reading to occur. Areas of the brain that process speech sounds, the sequence of letters in a printed text, and the meaning of words need to be trained to work together in order for a reader to automatically read the words on a page and subsequently make meaning from those words. Learning to read is truly a magical process.

In 2000, the National Reading Panel outlined five key components for effective reading instruction: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. To develop the neurological pathways in the brain necessary for skilled reading, these five components of reading need to be explicitly taught and practiced, such that they weave together to produce automatic and skilled reading.

At Park, reading instruction is rooted in research and the findings from the National Reading Panel. Lower Division teachers use a variety of programs and approaches to explicitly teach the five key components of reading. Although the emphasis of reading instruction may vary from grade to grade and from student to student at any given moment, Lower Division teachers deliver explicit instruction in all five components, supporting our students to become successful and confident readers.

Reading instruction at Park is also rooted in the deep knowledge that Lower Division teachers have of their students. Each fall, and during subsequent points of the year, teachers and Literacy Specialists formally assess the essential components of skilled reading using various assessment tools. Next, teachers and Literacy Specialists analyze the data, gleaning valuable information about a student’s literacy strengths and areas for growth. This data then informs instruction, whether that instruction occurs with a classroom teacher, a Literacy Specialist in a small group, or a Learning Specialist from Academic Support in an individualized setting. At Park, we recognize that learning to read looks different for each student and provide the appropriate level of support to help each student progress.

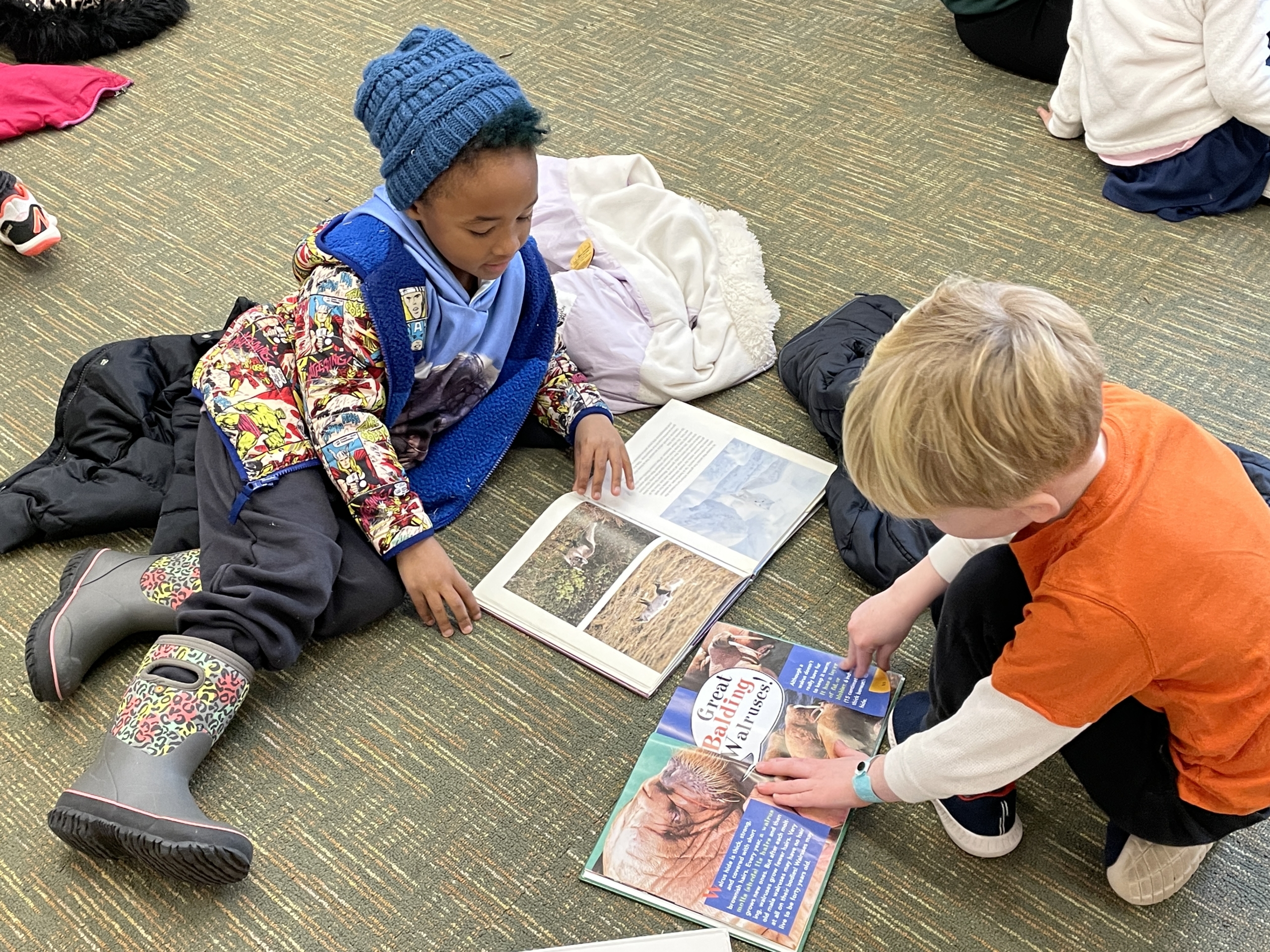

Perhaps most important of all, the primary goal of reading instruction at Park is to help all students develop a love of books and to identify as a reader. This love of reading is intentionally fostered through many aspects of a student’s day – from the books a teacher chooses to feature in the classroom, to weekly visits to the Library, to books read aloud shared during non-literacy times of the day such as Social Studies and Math. Books are everywhere, they are celebrated as tools for both learning and enjoyment, and all of our students are celebrated as the joyful readers that they are.

So, what does reading instruction look like in action? Let’s join a Grade 1 classroom to find out!

At the start of each reading lesson, teachers explicitly teach a skill or strategy to support their young readers. Recently, first graders were introduced to “King Ed” – the vowel-consonant-e syllable pattern. They learned that “King Ed” comes at the end of a word, reaching his scepter up and over a consonant and saying to the vowel, “Tell me your name!” The vowel listens, producing its long sound, such as in the word “bike.” Letter stories and mnemonics such as “King Ed” are engaging, fun, and help the learning “stick” for students as they learn the sounds and patterns of our language. Phonics is only as boring as you make it!

Following a whole group lesson, reading instruction continues in teacher directed small groups. Based on data, teachers identify short term goals for students, working with several small groups during a literacy period to reinforce, practice, and extend skills. As these groups are based on student needs, the area of teaching may vary from group to group. For example, one group might read a poem to develop fluency skills such as reading in phrases and with expression. Another group might read a book to practice comprehension skills such as making connections. A third group might read and spell words to reinforce a previously taught phonetic pattern. The small group structure allows each student to receive the instruction they need.

While teachers work with small groups of students, the other students in the class independently complete literacy centers, practicing and applying new and previously taught skills. For example, after learning about King Ed, first graders practiced reading and marking up words with the vowel-consonant-e pattern. Later in the week, they were tasked with spelling vowel-consonant-e words to match a picture, using their phonics and phonemic awareness skills to hear and represent the sounds in words. Students also write in journals, practice spelling high frequency words, use iPads for apps such as Lexia, and read a variety of “just right” and picture books.

Learning to read is a multifaceted skill that is gradually acquired over years of instruction and practice. At Park, we strive to develop life-long readers by leveraging research based practices, data from assessments, and knowledge of our students to deliver reading instruction that grows our students’ skills and love of books.

By: Alli Raabe, Park Literacy Specialist